One simply cannot come to this part of Mexico without noticing that mezcal flows here more freely than water. The bold spirit is king in the state of Oaxaca and you don’t have to go very far away from the capital to find yourself in agave country. Rows upon rows of spiky succulents cover undulating hills as far as the eye can see like a southern Napa Valley for the connoisseurs of this beautifully complex spirit.

Best enjoyed on an organized tour (you can’t possibly explore agave country without copious amount of tasting!), visiting for a day the nearby town of Santiago Matatlán is a must for anyone serious about getting to know this liquid gold. Although a small community, the town is considered the “world’s capital of mezcal” and seems to contain more distilleries than anything else! Our tour took us to a local distillery, Ilegal Mezcal, where we learned the basis of mezcal production which has barely changed over the past centuries.

The most significant factor influencing the taste of a mezcal is the type of agave from which it is made. With over fifty different varieties of agave, the range of flavors is substantial (contrary to tequila which is only made from one type of agave – the Blue Agave). Harvesting the agave starts first with chopping off the long spiky leaves to uproot the piña which can weight anywhere between ten to several hundreds pounds and carrying them back to the palenque (mezcal distillery).

Artisanal mezcal is a labor-intensive process which is why it isn’t cheap. Piñas are cooked in an earthen oven which is little more than a hole dug in the ground like it has been done for hundreds of years. Size of the oven, use of volcanic rocks to intensify the heat, and type and amount of wood used all influence the flavor profile. Here the piñas are buried under a tarp, covered in soil and left to cook for three to five days typically.

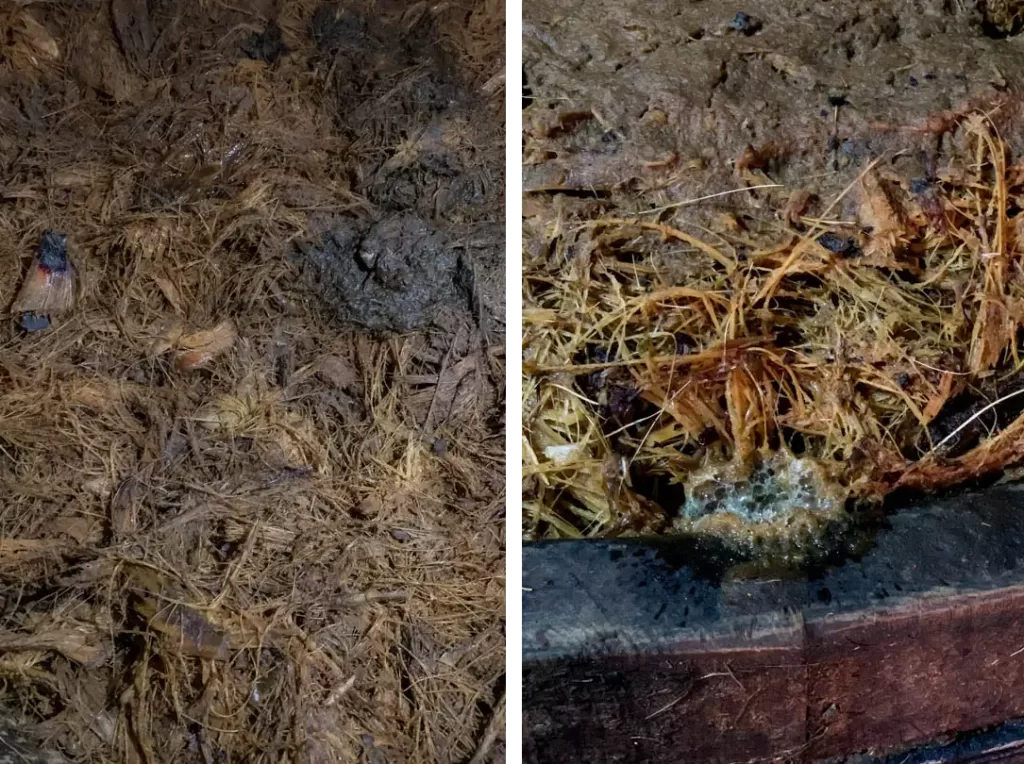

Once the piñas are cooked, they are crushed with a tahona, a large stone wheel attached to a central axle which is pulled around a circular stone cylinder by a horse, mule or donkey.

The resulting mash is then loaded into fermentation vats with water.

The period of fermentation will vary based on season, temperature, geography, etc. and another actor at play here are the wild yeasts in the open air of the palenque which are anything but controlled.

At the end of fermentation the mixture of water and crushed agave is called tepache, and is about 8% alcohol by volume. The tepache is loaded into small clay or copper pot stills to start the distillation process. Mezcal must be distilled at least twice to be exported (and to taste great as the 20 to 30% ABV of the first distillation isn’t really that palatable). To be certified, a mezcal must be at least 36% ABV and as high as 55% (most of the ones found in the US range between 40% to 50%).

After being lab-tested and certified (to ensure a quality and nonlethal product), the mezcal is bottled as joven (young), or put into barrels for aging. Voila! This was an oversimplified explanation of a primitive and fascinating process that differentiates mezcal from every other spirit on the planet. I’ve left out the hundreds of factors left in the hands of the expert mezcaleros to shape the final taste of their mezcal. If you’re curious and want to know more, I highly recommend you read “Holy Smoke! It’s Mezcal!” by John McEvoy – an excellent and detailed introduction I really enjoyed geeking out on.

Of course, the tour ends with a tasting (unlimited I must say!) to get a taste of what we had just learned.

Some fresh air was required afterwards to clear our spirits and our lungs of all the smoke (as lovely as it smelled) and no better ways here than to wander among the infinite rows of agave.

Rolling hills of spiky heads sparsely dotted with distilleries are reminiscent of wine country landscapes albeit with an attractive blueish tint closer to Provence than California.

A last stop at a local restaurant to help soak up the alcohol (with more mezcal to wash it all down) completed a wonderfully informative tour unique to the region. Salud!